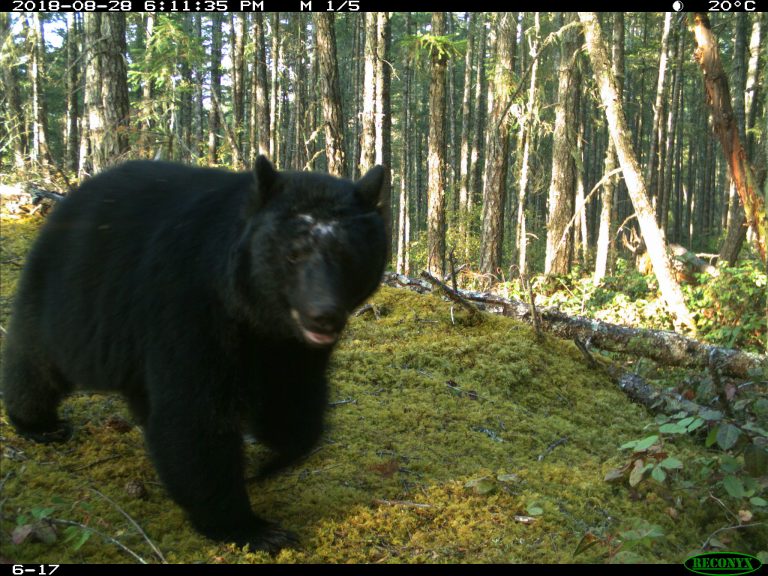

I have now been out to my fieldwork site 6 times spanning from June-October, and while locals and my camera traps both agree there is a lot of black bear activity, I have yet to see one.

I have camera traps set up in Sooke, a municipality west of Victoria on Vancouver Island. It is known for its parks, ocean basin, and an abundance of black bear-human conflict – three times that of any other municipality in the region. My project is looking at where black bears are spending their time in a gradient of human development, from urban to wild.

The abundance of large carnivores is on a different scale than the abundance of a similarly large but herbivorous animal like a deer. When people in Sooke say there are a lot of deer, they mean it in the sense that you will see at least one every time you drive longer than 5 minutes. They are in the centre of town, rural areas, and parks – popping up behind fences or in the middle of the road. In comparison, people know there are cougars somewhere out there on the island, but most haven’t encountered one themselves. Black bears seem to be somewhere in-between. Most residents have seen one, many see them multiple times a year, but they are just rare enough to be the subject of excitement.

This is what makes camera trapping so fun. Sure, it generates important scientific information, but in the thick of fieldwork or analysis, seeing your study species can give you the second wind you need to get through.

|

|

|

Additionally, camera traps provide an avenue of explaining my project outcomes to academics and non-academics alike in a way that is engaging and inspiring. These are close-up photos that don’t mirror normal or safe bear encounters where you hope to be far away and inside a house or vehicle. Our lab was recently talking about the phenomenon of “animal selfies” where people put themselves and wild animals at risk by getting close and taking photos. This is never recommended, but camera traps allow for a bit of the thrill of being near a wild animal without the risk to the bear. They allow you to see an animal with minimal human interference, just being curious without the edge of danger.

This idea of getting a window into the lives of bears is especially clear in my two favourite photos below:

Firstly, is this one image of twins play fighting. I have a sequence of photos showing this interaction running for three minutes, during most of which they are so closely locked together it is hard to tell which is which. Seeing this in person is almost unthinkable. If I saw cubs, no matter how cute, I would want to leave to avoid running into Mama Bear. Plus, the impact of my presence could have interrupted them. So being able to re-watch this scene over and over and share it with others is unique and special.

Secondly, bears are innately curious and guided largely by their sense of smell. So, when a novel object is introduced to their environment, they often go to check it out – with their mouths. This particular photo shows a bear pulling on the bungee cord holding the camera in place. It was also part of a sequence involving the bear putting the camera in its mouth. Luckily the camera was not damaged and only experienced a few minutes of cloudy photos from the bear slobber.

I’m headed back out to the field in January and can’t wait to see what photos I have waiting for me (and maybe a distant sighting of a bear from the safety of my car)!