Welcome to the Wildlife Coexistence Lab at UBC!

We are a group of researchers in the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Our research is focused on human-wildlife coexistence across multiple species and scales, with a particular emphasis on large-bodied terrestrial mammals.

The lab is led by Dr. Cole Burton, Associate Professor in the Department of Forest Resources Management, and Canada Research Chair in Terrestrial Mammal Conservation.

NEW MSc Defense !!

April 25, 2024

A huge congratulations to Katie Tjaden-McClement who recently defended her MSc Thesis ! Katie has worked hard to understand and evaluate large mammal species-interactions in the Chilcotin Plateau region of B.C. Specifically, she investigated whether disturbance mediated apparent competition (DMAC) was the main reason for decline for the Itcha Ilgachuz caribou herd as well as […]

NEW Lab Paper !

April 25, 2024

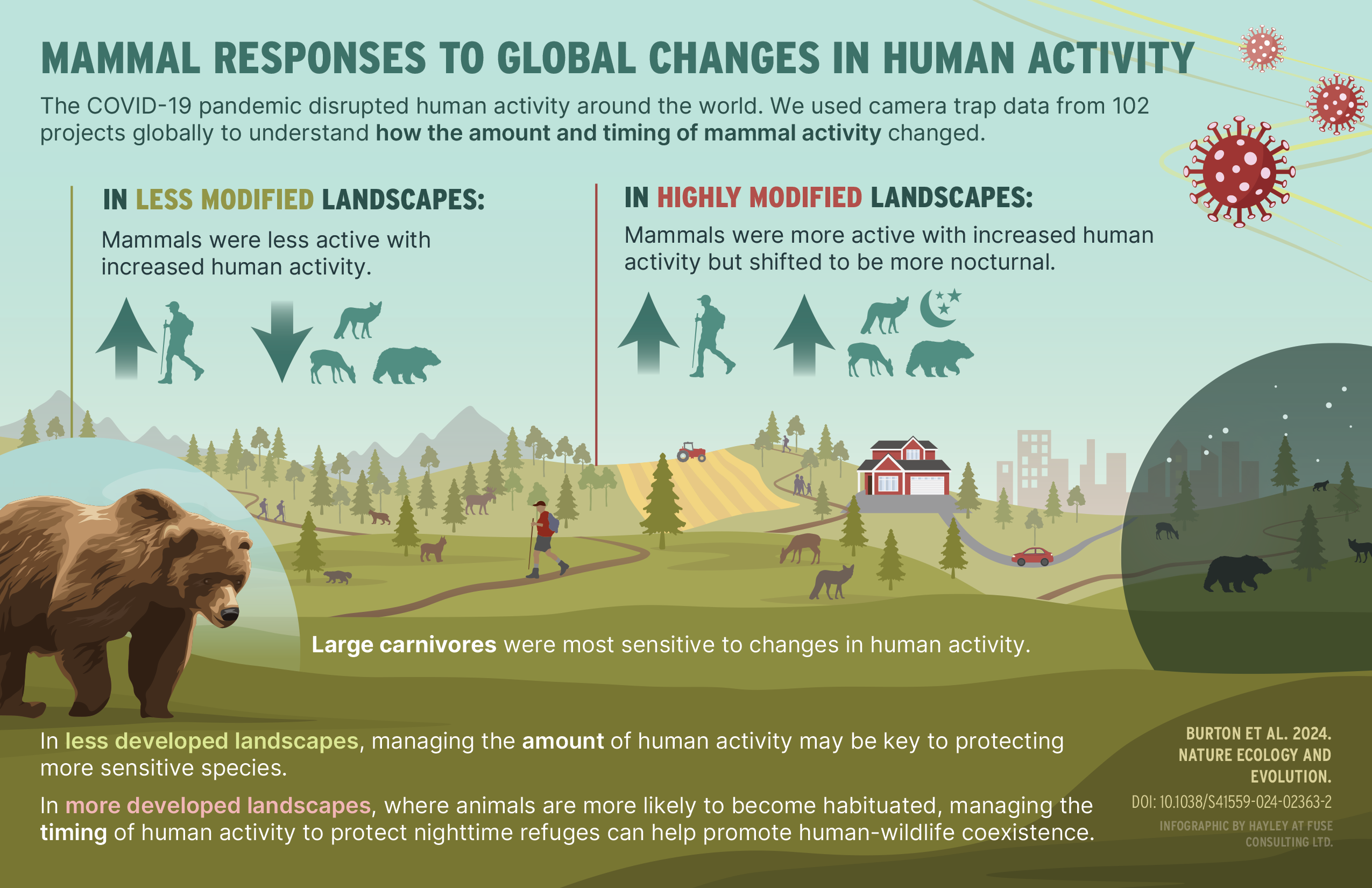

As a part of a huge collaboration between Dr. Cole Burton, former Wildco postdocs, Dr. Chris Beirne, Dr. Catherine Sun, and Dr. Alys Granados, UBC collaborator Dr. Kaitlyn Gaynor and many others, we recently published a global study that investigated the response of mammals to the COVID-19 pandemic. While the pandemic was a tragedy, the […]

WildCo PhD’s x2!!

April 13, 2023

We are absolutely thrilled to share that Dr’s Cheng Chen and Cindy Hurtado both successfully defended their PhDs last Thursday! Cindy and Cheng were some of the original WildCo Lab members, and are the first PhD students to come out of WildCo! Cheng’s thesis research focused on using a global camera trap dataset to look […]

Check out the WildCo Lab’s and Cole’s personal Twitter feeds and our Instagram for more information. Camera trap photos displayed on this webpage are collected by the WildCo Lab in collaboration with a diverse range of partners.