By Cheng Chen

Setting up protected areas is one of the fundamental approaches of in-situ conservation. But ecologists and conservation biologists are always wondering: do protected areas work for wildlife? In 2015, I spent 6 months in 6 protected areas located in a place called Xishuangbanna (pronunciation: “Sibsong banna”) in Southwest China and tried to answer this question.

A few words about Xisghuanbanna

Xishuangbanna is administratively unique: it is an autonomous prefecture in Yunnan province.

Unlike other places in China where the majority nationality is Han, more than 30% of the local population is Dai. Dai people are famous for their hospitality, ability of dancing and singing and, like most of Southeast Asia residents, Theravada Buddhism beliefs, which makes this place full of exotic elements.

More importantly, the southwest monsoon from May to October makes the climate of this place the same as most tropical countries. It is impossible to distinguish the typical four seasons, but rather, a year is roughly divided into dry and wet seasons. This tropical monsoon climate has brought a large tropical rain forest to Xishuangbanna, which also has the Mekong River flowing through. Although Xishuangbanna makes up only 0.2% of China’s total area, it has 66% of the bird species and 22% of China’s mammal species.

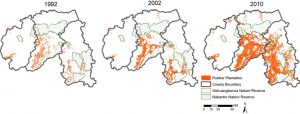

However, the large-scale rubber plantation, which began in the early 1990s, has eroded the large-scale tropical rain forest and highly fragmented the entire landscape of Xishuangbanna. That is to say, high-quality forests and habitats for wildlife barely exist outside the few protected areas in Xishuangbanna. This makes the question of protected area effectiveness for wildlife critically important.

How to assess the effectiveness of protected areas

The most intuitive approaches to evaluate the effectiveness of protected areas is to look at the counterfactuals, such as comparing the habitat (or wildlife species richness or abundance) before and after the establishment of the protected area. Since the data before the establishment of protected areas in this area were not well documented, the approach I used was to look at “space counterfactuals” rather than “temporal counterfactuals”. I selected 6 protected areas in Xishuangbanna, with differing levels of management intensity and protection. I used medium to large-sized mammals as indicators to find the relationship between protected area management level and mammalian diversity.

A local villager has a pet pig-tailed macaque (Macaca leonina). This macaque is listed as Class I protected animal of China.

Wildlife survey

So, the first step: I used camera traps to figure out the mammal bio-metrics in each protected area. I “captured” 22 medium to large-sized mammals in total. The species richness and abundance of mammals in each protected area was estimated by using Royle-Nichols (‘RN’) latent abundance N-mixture models and multi-species occupancy model.

Management level?

The next step was to estimate the management level of the protected area. But how can we estimate the management of the protected area? The method I used was to interview the local villagers living around the reserves. The various ethnic groups in Xishuangbanna have a long history of using natural resources. They used to cultivate this land by slash-and-burn agriculture, and they currently hunt and harvest timber and non-timber products in the forest. The success of a protected area depends on whether management can establish a good relationship with local residents and whether authorities (i.e. park and government) can change their behavior and habit of using natural resources.

I used questionnaire surveys to estimate local villagers’ perception of punishment that the park meted out to rule breakers and outreach activities of protected areas. I found that the abundance of large mammals was positively correlated to the perception of the park punishment, and the species richness of mammals within a park was positively correlated to the local perception of outreach frequency of the protected areas. This result implied that protected areas can be effective as long as there is sufficient management effort put into it. This research has recently been submitted to a journal and is under review. Please stay tuned! (Fingers crossed!)

Human perspective of conservation

Today, more conservation biologists have recognized the importance of the social aspect of conservation. Human beings are an important part of conservation, because conservation biology is seeking to change human behavior. I spent a lot of time in the summer of 2015 drinking with my village fellows and chatting with the head of each village. People that live in the villages shared their joys and sorrows with me, through the help of a translator. Wildlife conservation in Xishuangbanna still has a long way to go but I really feel that local people’s understanding and attitudes towards protected areas and wildlife in general is indeed becoming better.