A human-wildlife conflict is simmering in the Peace River Region in northeastern British Columbia.

On March 21, the BC government released a draft Partnership Agreement for the recovery of the Central Group of southern mountain caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). The draft outlines immediate actions to protect the six caribou herds in the Central Group. While many are celebrating the new plan as a new step on the path to caribou recovery, others are less than thrilled. The agreement’s release resulted in public outcry in local communities: criticisms of the government for closed-door decision-making, calls for continuing wolf control, and expressed fears of job loss and restricted backcountry recreation. In efforts to quell concerns and manage miscommunications, BC has extended the community consultation period until May 31.

How did we get here?

Caribou declines

Like caribou across Canada, Central Group herds have shrunk dramatically in recent years. There are now approximately 220 caribou remaining in this population, down from 800 in the early 2000s. The cause of their decline is complex, but ultimately leads back to growing resource extraction in the Peace region. Logging resets the forest to early seral vegetation (fast growing, disturbance tolerant plants), providing forage for deer and moose and thus supporting larger populations of these ungulates. Growing prey populations in turn bolster predator populations, resulting in more wolves on the landscape. This landscape has further been reshaped by seismic exploration for oil and gas, which creates linear features that act as movement corridors for predators to move into caribou habitat. Although caribou aren’t typically primary targets of predators, linear features increase the likelihood of a wolf-caribou encounter – or the likelihood of predation. Caribou historically retreat to high elevation and mature forests to escape predation, but with more predators and disappearing old forests, this avoidance tactic isn’t as effective as it once was. Thus, the cumulative effects of recent changes – forest harvest, linearization, more deer, moose and wolves – create a dangerous landscape for caribou.

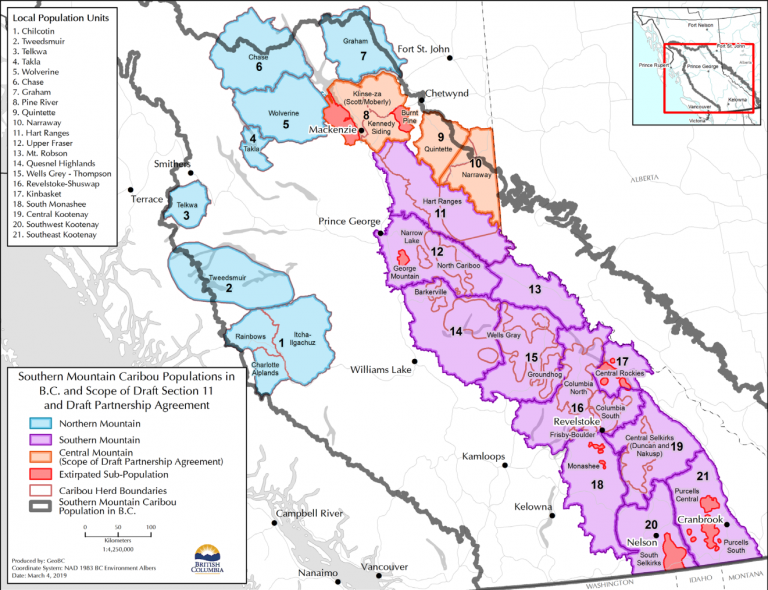

Southern Mountain Caribou populations in British Columbia, from the Caribou Recovery Partnership Agreement Overview.

Caribou protection

Southern mountain caribou were listed as threatened under the Species At Risk Act (SARA) in 2003, creating a legal framework under which the Canadian government has an obligation to protect species facing declines from human activity. In May 2018, 10 herds of southern mountain caribou were found to be in ‘imminent threat’ of extinction, providing grounds for the federal government to issue an emergency order to halt all industrial development in critical caribou habitat. To avoid this outcome, which could jeopardize local economies, the province set about drafting conservation measures for southern mountain caribou: a Conservation Agreement between BC and Canada for southern mountain caribou, and the Partnership Agreement between BC, Canada, West Moberly First Nation and Saulteau First Nation. The two First Nations have been leaders in caribou conservation in the area, and both the provincial and the federal governments have responsibilities to consult First Nations on projects affecting their lands under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Partnership Agreement applies only to the six herds of the Central Group, while the Conservation Agreement applies to all herds of southern mountain caribou in British Columbia. The two agreements were released as drafts, and the province opened a community consultation period (originally scheduled for six weeks) to hear feedback from the public.

Community fears

Immediately, the province received pushback from Peace Region municipalities. The chief concern was for the impact on the economy: fears of lost forestry jobs spread like wildfire in places like Chetwynd, where forestry is one of the main employers. Another main worry included recreational restrictions, cutting off access to the awe-inspiring landscapes enjoyed by most locals. People came to the Region for the industry and stayed for the freedom of exploring the vast expanses of back country. In the eyes of locals, trading the region’s two foundational attractions for caribou protection is too high of a price to pay. In addition to these fears, many expressed frustration at the lack of communication and community involvement throughout the drafting of the agreements. At their worst, these grievances manifested as racist backlash against the two First Nations. Crucially, many of these fears and frustrations are based in misinformation as a result of cutting key community stakeholders out of the caribou conversation. As well as extending the consultation period, BC premier John Horgan acknowledged the province had neglected communications with affected communities and appointed a community liaison to oversee ongoing discussions.

A boreal woodland caribou in northeastern Alberta, where caribou populations face habitat loss and increased predation from industrial development similar to that faced by southern mountain caribou in BC.

But what’s actually in the agreements?

The current agreements are drafts to be finalized and implemented following the current consultation process. While the Conservation Agreement is stuck in planning phases and lacks actionable conservation measures, the Partnership Agreement maps out landscape protections to be implemented immediately. These protections include temporary suspension of new industrial development in some areas, complete habitat protection in others, as well as measures to decrease long-term landscape disturbance in caribou habitat. While some of these protections may result in reductions in forest harvest, the decrease would be less than 4% the total annual harvest across two timber supply areas and one tree farm license. Further, the agreement sets out an additional engagement process to discuss motor-vehicle restrictions in critical areas, but does not implement restricted backcountry access. The Partnership Agreement also outlines continued predator management and maternal penning to provide immediate relief to the dwindling herds, as well as plans for an Indigenous Guardian Program to monitor caribou according to traditional practices.

Moving forward

Like many conservation controversies, caribou in the Peace Region has been frequently framed in terms of perceived dichotomies: growing the economy vs. conserving the environment, and interests of rural populations vs. those within urban centres. However, in moving conservation efforts forward it is vital to look beyond seeming contradictions to find common ground. This process is a difficult one, requiring open-minded communication grounded in compassion and patience, but often reveals that perceived dichotomies share common roots: the desire to keep and grow relationships to place. It is these relationships that fuel both the desire to protect caribou as well as to protect industry jobs that sustain local communities. In continuing these consultations, it is crucial that this common ground is acknowledged and saved from drowning in inflammatory language, so that we may move past human-wildlife conflict to human-wildlife coexistence.

If you would like to participate in the consultation process, comment on both the Conservation Agreement and the Partnership Agreement here.